Dossier Highlights

- Grants, fellowships and awards

- $370,000 in grants (including NSF external grant)

- 2018 IU Trustees Teaching Award

- Research support, workshops and consulting

- 2017 appointment to Co-Directorship of Institute for Digital Arts & Humanities

- 6 Getting Started In Digital History workshops for the American Historical Association annual meeting

- Recruited leaders for 10 individual sessions/year

- Managed start-to-finish workshop experience for more than 600 participants across all 6 years

- More than 30 digital-methods workshops personally delivered since Fall 2015

- More than 300 digital-methods or digital-pedagogy consults for faculty or graduate students since Fall 2015, including consults for 20 different affiliates of the Department of History

- Graduate teaching and mentoring:

- Digital-history course developed and revised three times, once for dual graduate-undergraduate enrollment, once to include service-learning History Harvest project

- 10 graduate students mentored in digital history methods, including 2 dissertation committees and mentoring of 6 IDAH graduate assistants (2 from history)

- 6 graduate-student co-authors

- Undergraduate teaching and mentoring

- 4 new courses developed for history, including 2 Digital History courses focused on history of Indiana. 3 courses revised multiple times, 2 with major adaptations to include service-learning History Harvest project

- 5 students returning from courses to work independently on digital projects

- 3 undergraduate-research-intern mentoring experiences

-

A Guide to the Personal Statement and Dossier

I drew heavily on the American Historical Association’s Guidelines for the Professional Evaluation of Digital Scholarship by Historians, and on the public-dossier model that is particularly visible in the work of Sharon Leon and Kathleen Fitzpatrick, as I considered the form and structure of this dossier.

The AHA guidelines ask all historians to:

explore and consider new modes and forms of intellectual work within the discipline and to expand their understanding of what constitutes the discipline accordingly…. including new digital short-form genres such as blogs, social media or multimedia storytelling, developing and using new pedagogical methods, participating in strong activist forms of open-access distribution of scholarly work, or creating digital platforms and tools as alternative modalities of scholarly production.

I invite you to share in that joint mission by exploring this interactive personal statement, with in-text representative samples of public-facing supporting documents in the form of embedded links, screen captures, multimedia and interactive content. Representative samples of documents with confidential information, (solicited letters for teaching and service, course evaluations, internal university documents, email with contact information other than my own) were made available to external reviewers via a shared-document folder (available on request from histca@indiana.edu) and are in IU’s eDossier system.

Overview

When I was transitioning from industry to academia in the mid-2000s, someone asked me how I would define success in an academic setting. I thought at the time that it was a throwaway question, and I gave an equally offhanded answer:

If one person takes one small positive thing away from working with me, and I from working with them, once a term each term, I’d consider that a success.

In the years since, that offhanded answer has come to mean a great deal more.

Helping one person at a time has become part and parcel of the service and teaching that defines my current appointment as Clinical Assistant Professor of History. This emphasis on mutual support and learning has shaped my understanding of how I fit into the educational mission of Indiana University as a teacher, as a colleague, as a research-center administrator, and as a pedagogy and digital-history researcher. I’m fortunate to have been well supported in these endeavors by colleagues in the medieval history field whose careful planning has supported development of the courses in which I do my digital-methods research; by a Department of History that has facilitated me in incorporating digital history into its course offering and research goals; and by a campus community that has privileged new approaches to humanistic inquiry and thus eagerly taken up many of the initiatives that I have been part of advancing.

Since beginning this appointment in Fall of 2015, I have sought to blur the boundaries between service, teaching, and research in digital methods by offering a clinical practice based on the integration of evidence-based digital-humanities pedagogy and innovative digital-history methods. My work in these joint spaces for the Department of History led to a 2017 appointment as Co-Director for Indiana University’s Institute of Digital Arts and Humanities (IDAH, with my co-director Michelle Dalmau), in which I’ve been able to extend the integrated digital-humanities methods activities that I pioneered and supported within the Department of History to a wide range of arts & humanities practitioners at Indiana University–Bloomington and beyond.

A case study

Net.Create for history reading comprehension and powerful but easy-to-use network analysis in history

Digital historians integrate digital methods into the exploration of change and continuity over time in a variety of ways. Analytical approaches used by big-data analysts help historians find patterns, fill gaps, and look for new questions in historical documents. Interactive modes of presentation afford historians new ways to present historical scholarship and to engage with new publics. My teaching and service work draws on both the analytical and presentational traditions of digital history.

Many of the items in the portfolio speak to more than one aspect of these digital-methods approaches, to more than one element of the appointment, to more than one of the communities in which I serve and teach, and to the need to sustain a project over a long period of time. As each person with whom I work offers suggestions or has additional needs for each of the projects in which I’m involved, and as the fields of education and digital history innovate and change over time, I follow suit. As I learn and innovate with my colleagues, I stay on the lookout for potential iterations that might improve each project for the benefit of my colleagues and students alike.

One project in particular provides a microcosmic view of the integrated, longitudinal approach around which I’ve structured my appointment: Net.Create, a grant-funded tool for humanists who want to explore connections in their research. Experienced humanists walk into a new reading with a framework in place—a general narrative of periods, geographies, and theories into which we can easily fit, and evaluate the significance of, new information. Students are often novice readers, and they haven’t yet built that framework for themselves. Net.Create is designed to bridge that gap.

I designed Net.Create, at first independently and then with my research partners, from the ground up to support novice readers coming to grips with the complex task of close-reading a humanities text.

- Students work in small groups to collect a set of notes about the interactions between people, places, things and concepts in a text.

- Each note is entered into Net.Create, which uses simple web-based forms (like those you might see in an online shopping cart) to prompt the inclusion of citations and more detailed specifics about the historical significance of each entry.

- As groups enter these notes, various pieces of the note are also reproduced in visual form: each thing is a circle (a node), and each connection they make draws a line (an edge) between two circles that interact.

- With each entry, nodes with many edge connections become visually larger and a network “gravity” begins to develop, pulling larger nodes to the center and distributing smaller connected nodes around them. These two features provide immediate feedback to the students as they try to sort through the significant figures in a new-to-them text.

The collaboration in a Net.Create activity has two layers. Within their small groups, students organically begin to discuss what should be in the network, how things in the network interact, and how to describe those interactions. At the same time, they also get prompts from the activity of the whole class, since each group can see all of the other groups’ entries appearing live. New nodes, edges, and notes from other groups can provide inspiration for groups who are confused or lost and need a little help refocusing. When students leave the classroom, the network and all of its notes are still accessible, as a unique and dynamic study guide produced by students with instructor guidance.

I knew that doing my small contribution may have seemed small but everyone else doing the same provided an extremely useful and beneficial network for the entire class.

–Student in H213 The Black Death, Spring 2020 on their Net.Create experience

As a network-analysis tool, Net.Create is ground-breaking because it allows many users to collaborate in real time as they build an interactive network dataset and visualization easily and with minimal technical skill. As a digital-humanities pedagogy tool, it is even more valuable because it allows an instructor to see what novice readers are drawing collaboratively from a text in real time. Instructors can immediately adjust and respond to those reading practices, and re-use the resulting network and its notes for the remainder of the class experience with that text or texts.

Net.Create’s first iterations were confined to the walls of my classroom. My hope at the very beginning—and the reality now—is that Net.Create’s subsequent forms would support teaching and research, mine and others, both here at IU and elsewhere. The integration of teaching, research, and service that Net.Create represents is an example of the groundwork in a variety of digital-history environments that I have established in my clinical practice as a historian. To date, Net.Create has supported:

- innovative digital-methods pedagogy. In addition to 6 of my own classes, Net.Create has supported digital-pedagogy opportunities in a variety of other instructional settings. These settings range from community-college undergraduate classrooms to digital-humanities research workshops to a citation network of learning theory built by conference-goers overseas.

- grant-funded activity. It was the primary platform for a successful digital-tools grant from the NSF on which I am the PI and an unsuccessful one that’s in the process of resubmission to the NEH (on which I will be a Co-PI). A new grant collaborator spearheaded a grant that uses Net.Create to help students and teachers find inter-personal connections as a way to support culturally relevant pedagogy in 6th grade math classrooms (on which I am a Co-PI).

- educational research. It forms the core of an educational-research program that explores reading comprehension, historical thinking skills, and student engagement in both my and other instructors’ history classrooms. We are currently on our 4th round of data collection and have several published and in-progress papers.

- public humanities in undergraduate service learning. It was the primary tool for students who wanted to explore the connections between audience-contributed material-culture objects in a public-engagement project rooted in a Fall 2019 History Harvest at IUB.

- affordable digital-humanities research. Net.Create is open-source, which means it’s free and other software developers can contribute to it. As a result, a number of students, both undergraduate and graduate, and faculty from fields that include history, musicology, media studies, and education are currently using Net.Create for their own research. One of IDAH’s former graduate assistants is using Net.Create to support network-analysis workshops at UC Santa Cruz, and we are currently surveying users nationwide as we explore the outlines of a next-stage grant for more widespread research use.

- workshops and professional development. Net.Create supported a number of workshops designed to teach network analysis as well as digital-humanities pedagogy approaches, both on the IU campus through the Institute of Digital Arts and Humanities (IDAH) and on a national and international basis

- online teaching. I anchored the remote-learning experience of students in a class on The Black Death on Net.Create during the COVID-19 pandemic, which one student described as “effing brilliant”. Because preparation for a history-learning study was already in place, we were also able to document the student learning-outcome experience for an article in the June 2020 special issue of Information and Learning Sciences. I plan to use these spring experiences and the results of that study to prepare better online-learning activities for students in the future.

With Net.Create, I have a digital-methods platform in which I can experiment, refine, and reshape not just the activities but the platform itself to explore how I can continue to improve my support for student learning and colleague research.

Research in Teaching: Digital-methods pedagogy

Research conducted in history classrooms has given me a way to structure a significant portion of both the teaching and service components of my clinical activities. These research projects center on an evidence-based practice that combines learning theory with practical teaching and technology considerations for historical inquiry. The digital methods that are at the center of my research questions, however, are only one part of the story. Each of these research projects builds on one aspect of my primary learning goal for students: being able to independently develop their own historical arguments. That larger category covers a number of specific historical thinking skills that I want students to have:

- recognizing different perspectives in primary sources

- developing context for a historical event using primary sources

- integrating secondary sources in a consideration of historical perspective and context

- developing the writing, presentation and organizational skillset to communicate their work.

While each of these 5 projects got their start differently, all of them blend two approaches to educational research on history learning:

An approach grounded in the scholarship-of-teaching-and-learning (SoTL) explores history learning through the lens of our own disciplinary training and aims to reproduce the values and skills of professional historians. SoTL explorations are primarily geared toward understanding which specific historical thinking skills are best supported by digital methods (and which aren’t). A secondary focus demonstrates how instructors at the college level might draw on the results of these articles for their own practical purposes. With a SoTL approach, I generally begin with a digital method that meets some classroom or engagement need and then develop an activity that uses the elements of that digital method most directly suited to developing student historical thinking in a particular way. Partnerships with instructional consultants and fellowships from in IU’s Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning have resulted from these SoTL approaches.

An approach grounded in the learning sciences looks at how disciplinary activities are informed by cutting edge theories of learning, collaboration and educational tool and activity design. In particular, I am interested in activity theory, which explores how learning is shaped by the differences between novice and expert discipinary practices and how the tools to which we have access and the ways in which we interact in a classroom can help bridge that novice-expert gap. I’ve narrowed that activity-theoretical lens to three specific areas of interest. First, I want to understand how individual student learning is shaped by interactions with other students and instructors. Second, I explore how historical thinking is shaped by the organization of face-to-face and computer-mediated activities, with a particular eye to the many different physical and online classroom spaces in which those activities take place. Finally, I explore how particular digital-humanities methods map to particular historical-thinking skills. With a learning-sciences approach, I generally start with a perceived gap in novice-expert historical thinking and apply activity theory in the design of skill-building activities to bridge that gap. This approach makes it easier to identify which tool-building or digital-method approach will best support my learning goals. Faculty affiliations in the IU Learning Sciences program, and as a research collaborator of the Center for Research on Learning and Technology (CRLT) within the IU School of Education, have resulted from the successful incorporation of these learning sciences theories and methods.

The blend of these two approaches allows me to better accommodate the messiness of the classroom setting as a site of evidence-based educational research, so that each of the approaches pioneered in these studies can speak to, and be useful in, a variety of teaching environments. The mixed approach also serves as a bridge between the teaching and service portions of my appointment by providing practical insight into which tools support digital-methods activities best and how those tools might be modified to suit the needs of digital-humanities practitioners at all levels. For instance, with Net.Create, the history pedagogue in me was focused on how difficult it can be for students to reconstruct historical context in an unfamiliar reading; the learning scientist wanted to explore the specifics of a collaborative computer-supported activity in which each element, including user-friendly software with carefully chosen features, was designed from the ground up to support students as they engaged in reconstructing historical context.

In each of the following five projects, I have tried to strike a balance between my interests in digital methods for historians, the practical needs of historians in the classroom, and the evidence-based understanding of how these digital-methods approaches work to support students as they learn.

-

Net.Create Network Analysis to Support Reading Comprehension

Net.Create was designed to help students improve their reading comprehension as they explore the complexities of historical significance in long primary and secondary sources. I first tried it using Google Forms in nascent form in H213 The Black Death in Fall of 2015. Since then, it's been a platform for educational research in more than 10 classrooms of varying size and level, from introductory undergraduate survey to graduate theory courses. The custom tool we began to develop in 2018 is now robust enough to support faculty-led digital-humanities research projects.

Net.Create began in my Fall 2015 H213 The Black Death course when I designed and developed a single-session network-analysis activity to help support student reading comprehension of historical monographs. A combined software program and activity, Net.Create asks students to document the connections between people, places and events in a complex historical source (either primary or secondary; we have collected data on on how the activity supports student understanding of both). Students can then use the network and its resulting set of notes as a reference as they read the entire source and use it as evidence in a historical argument. Clear labels help students find people and groups. Size and positioning helps students judge significance (large = frequent appearances, central = more connections to other figures). Network gravity helps students see how one well-connected person compares to another in terms of number of interactions; click and drag a person/node; central nodes with follower-nodes that don’t move quickly can highlight smaller nodes that have conflicting connections.

One of the most rewarding moments in my time at IU came when one student in a group announced out loud to their group early on in a Net.Create activity that they didn’t want to participate. In many group activities, such a pronouncement can derail the whole group. In the Net.Create activity, this student suggested not entering any nodes but instead adding edges to nodes entered by other student groups, an approach I then encouraged. That group went on to work steadily for the duration of the 40-minute activity to improve the class’ shared network. As a result of their engagement, the group members performed well individually on the reading responses that followed the activity. I drew on that experience and re-centered 5 of the 7 weeks of remote-learning activities for H213 The Black Death around Net.Create; 60% of the 93 students noted that participation in Net.Create helped them feel more connected to their classmates and helped them to see perspectives in the readings they might otherwise have overlooked.

Since Net.Create’s initial funding (internally from IU and from the NSF) in 2018, we have collected data in more than 10 classrooms of varying size and level, from introductory undergraduate survey to graduate theory courses. The same tool and process has been used in 4 history undergraduate courses for a variety of historical thinking purposes. I’ve also helped adapt the tool to support a number of different research environments, including 2 faculty projects, 2 now-complete PhD dissertations in history and musicology, several undergraduate research projects, and several research workshops. The project team has written a number of peer-reviewed conference-proceeding papers. One of these was extended to a full-length journal-article manuscript and submitted in early august of 2020. A second peer-reviewed article looks at the use of Net.Create for distance learning for a special issue on the COVID19-induced Spring 2020 shift to online teaching in higher education. Net.Create has also been the site of a significant effort in graduate-student mentoring. A number of papers and peer-reviewed conference proceedings feature graduate students as first authors or co-authors.

Finally, Net.Create has provided a rich environment in which to explore ongoing professional-development goals for my own teaching and digital-methods approaches. One example, a webinar for the Mosaic Initiative, puts that self reflection on display for other instructors who are working through their active learning in many different kinds of classrooms with many different class sizes.

Project Role: Principal Investigator, project manager and software co-designer. Managed team of 6 collaborators, plus software firm, and took the lead in developing long-term research questions, grant writing and publication development. I am a software co-designer, working with the team on user interface and data-presentation questions, and I undertake software-development tasks occasionally as budget and time demand. I am also the primary designer for in-classroom activities and the primary contact for training and installation for researchers who want to use Net.Create for their own work.

Grants:

- August 2018 NSF #1848655 EAGER grant recipient: $300,000 for Net.Create, a new network analysis tool and classroom activity system to support history reading comprehension, recall and argumentation. Read the full grant.

- January 2018 $60,000 internal grant designed to help develop a project prototype.

Publications:

- Kalani Craig, Megan Alyse Humburg, Joshua Danish, Maksymilian Szostalo, Cindy Hmelo-Silver, Ann McCranie, “Increasing Students’ Social Engagement During COVID-19 with Net.Create: Collaborative Social Network Analysis to Map Historical Pandemics During a Pandemic”, Information and Learning Sciences, Special issue (“Evidence-based and Pragmatic Online Teaching and Learning Approaches: A Response to Emergency Transitions to Remote Online Education in K-12 and Higher Education”), July 17, 2020.

- Kalani Craig, Joshua Adam Danish, Haesol Bae, Maksymilian Szostalo, Megan Alyse Humburg, Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver, Ann McCranie, “Net.Create: Network Analysis in Collaborative Co-Construction of Historical Context in a Large Undergraduate Classroom” at the 2020 annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, initially scheduled for April 17-21, 2020 (conference cancelled, peer-reviewed conference proceedings in press).

- Kalani Craig, Joshua Danish, Ann McCranie, Megan Alyse Humburg, Maksymillian Szostalo, Cindy Hmelo-Silver “On Feedback Loops: Digital-Pedagogy Research and Digital-Humanities Research in DH Tool Building” at the ACH2019 Conference, Association for Computing and the Humanities (Pittsburgh, PA), July 24, 2019.

- Haesol Bae, Kalani Craig, Joshua Danish, Cindy Hmelo-Silver, Suraj Uttamchandani, Maksymilian Szostalo, “Mediating Collaboration in History with Network Analysis”, in A Wide Lens: Combining Embodied, Enactive, Extended, and Embedded Learning in Collaborative Settings, 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) 2019, pp. 1438-1440 (June 2019).

- Kalani Craig, Haesol Bae, Joshua Danish, Ann McCranie, Suraj Uttamchandani, Maksymillian Szostalo, Cindy Hmelo-Silver , “Building Temporality and Textuality: Scaffolding History Reading Comprehension with Net.Create, an Interactive Open-Source Network An alysis Tool” at the XXXIX Sunbelt Social Networks Conference of the International Network for Social Network Analysis (Montreal, Quebec, Canada ), June 20, 2019. Ajudicated award for conference’s best poster

- Kalani Craig, Maksymillian Szostalo, “Building a Bishop’#39;s Network: Reshaping Network Analysis to Understand Episcopal Agency in Serial Biography” at the 54th International Congress on Medieval Studies, Medieval Institute, Western Michigan University (Kalamazoo, MI), May 9-12, 2019.

Current activity: The Net.Create team finalized a grant submission to Spencer Foundation in November, 2019 (Neri, et al; pending), in which we hope to take Net.Create into 6th grade math classrooms to explore whether network analysis of interpersonal interests can be used to help at-risk students get engaged in the process of math learning. My goal as part of the project team is to look at how activities that started in history classrooms and support historical thinking provide structure for STEM learning (when generally the narrative goes the other direction). This effort will also support the ongoing development of the Net.Create tool which I continue to feature in my courses at IU. In addition to educational-research studies like this one, we used Net.Create in 4 classrooms in Fall of 2019 (2 of my own classrooms) and an additional 4 in Spring of 2020 (1 classroom was mine).

One of these–a webinar for the Mosaic Initiative’s Faculty Research Series–combined work done in active learning classrooms with several of the Net.Create research endeavors to offer a system for transitioning lesson plans from one classroom to another, regardless of the available technology, seating arrangement or class size. “Using Activity Theory to Design Technology-Based Activities For Any Classroom”, Mosaic Initiative Faculty Research Webinar Series, October 11, 2018. https://mosaic.iu.edu/research/research-webinar.html (see video, right)

Several sample networks that show Net.Create outcomes in guided classroom activities are available at NetCreate.org and two undergraduate-research networks using Net.Create are available at NetCreate.org

-

Analog Tools in Digital History Classrooms

Not everyone likes actual technology as much as I do, but many instructors still feel as though they need to address it in their classrooms in order to keep their students engaged or keep their teaching fresh. This article details the learning outcomes of several activities that teach the underlying approaches behind text analysis, network analysis and mapping, but with sticky notes and chalkboards, so that students and instructors alike can get familiar with digital methods and then learn the tools later.

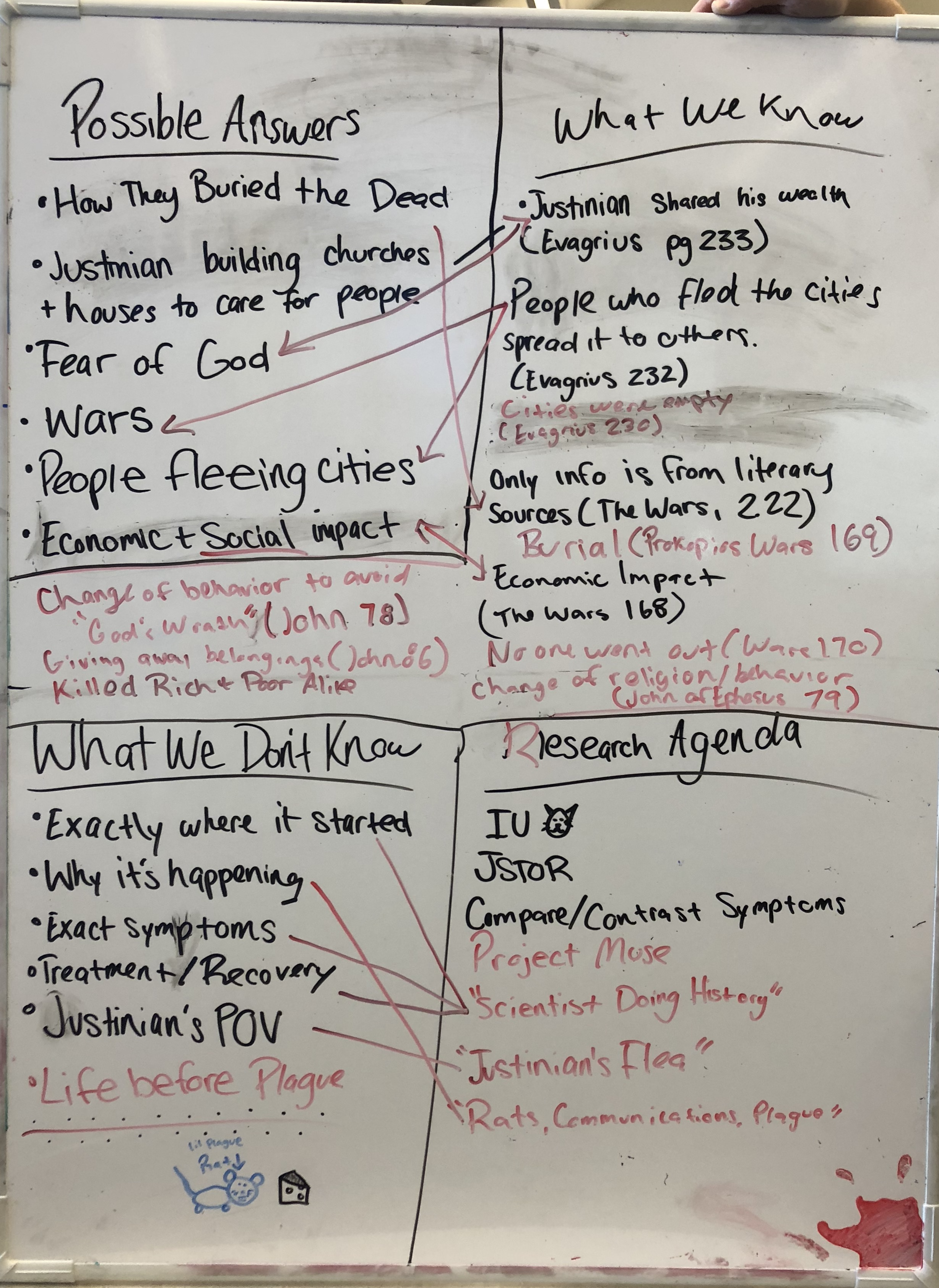

This SoTL case study was designed to provide support for instructors who want to incorporate new methods into their teaching practice but lack the classroom environments, the comfort with technology or both to do so in an entirely digital way. In it, I use activity theory to explore the use of blackboards, whiteboards, and poster paper to teach historical thinking through the application of several different digital methods. Each digital method supports different historical thinking skills: text mining for reading comprehension, mapping for historical context and network analysis for historical interaction. For instance, student produced maps using Ibn Shaddad’s Third Crusade narrative of Saladin’s life with different purposes (geographic context, frequency/significance of mention, and geography/emotional ties), and then discussed the differences and overlaps they found, rooting their discussion in both the maps and the text.

Since its publication, the article has been downloaded 730 times.

Project Role: Individual researcher. I designed the activities and the research study.

Publications:

- Kalani Craig, “Analog Tools in Digital History Classrooms: An Activity-Theory Case Study of Learning Opportunities in Digital Humanities”, in International Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 11: No. 1, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2017.110107

Current Activity: This study is the bedrock of my intro-to-digital-humanities teaching. I use it in my own classrooms (most recently H301 in Fall of 2019), for teaching algorithmic digital-history thinking as a guest teacher in other people’s classrooms, in workshops (most recently, IDAH’s August 2019 annual introduction to teaching DH), and in invited talks (most recently, a Feb 2020 visit to Baylor University). Colleagues have also used it in their courses and workshops.

-

History in 140 characters

Productive educational use of Twitter in the classroom is a particularly germane area of study for digital humanists, who consider Twitter a central piece of their community-building practices. For this study, I asked students to practice historical context-building and empathy in a discipline they often encounter as passive listeners in a large lecture course by taking not one historical perspective but several at the same time using a custom-built Twitter-like platform.

Click-bait headlines that tackle the modern phenomenon of social media often rail against the stultifying effects of too much Twitter. At the same time, productive educational use of Twitter in the classroom is a particularly germane area of study for digital humanists, who consider Twitter a central piece of their community-building practices. One claim digital humanists make for using digital methods in the classroom is that these digital environments are more familiar for students living in a digital world and thus provide a bridge between the familiar modern world and the unfamiliar context students encounter in history. This study, which is firmly situated between SoTL and traditional educational research, looks at specific claims about social media tools like Twitter as a medium to transform student comprehension of historical language, to emphasize accuracy in that reading comprehension, and as an end goal for both of these reading comprehension exercises, encourage historical empathy by asking students to actively take not one historical perspective but several at the same time.

In groups of 6 in a 96 person classroom, students reimagined Prokopios’ biography of Justinian by Tweeting from three perspectives: as Prokopios, as a gossip columnist, and as an objective news-media organization. Their Tweets included responses to other groups’ posts, which prompted small-group face-to-face interaction and large-class computer-mediated interaction focused on discussing the extent to which they had to exaggerate or mediate Prokopios as a way of understanding his reliability as a historical source, not in a simplified way but as a factor of the specific piece of evidence being evaluated.

In the first wave of Tweets, students included substantive interpretive information in 66% of their Prokopios Tweets, and 18% of the Tweets had errors. After the activity, 73% of the Tweets were substantive and errors had been reduced to 8%. Twitter situated the goal of reading comprehension in a modern medium that requires rapid repurposing of content. The activity’s explicit emphasis on the citation practices that govern published history research imparts a clear purpose for students’ interaction with, dependence on, and fodder for the interpretive historical-perspective acts being performed by their peers. I’ve used this activity in classrooms since 2014 with four different sources, and each time, it is both a personal delight to work with students who jump in and engage in the process and a lightbulb moment for many students who expect to extract historical facts from sources rather consider primary sources as collections of documents written by people whose different life experiences shaped their writing.

Project Role: Individual researcher. I built a private Twitter-like software tool from scratch and designed the activity and the research study around the tool.

Publications:

- Kalani Craig, “History in 140 characters: Twitter to Support Reading Comprehension and Argumentation in Digital-Humanities Pedagogy”, in The Emerging Learning Design Journal 5.1 (Special Issue: Digital Humanities), June 2017. http://eldj.montclair.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ELDjV51IS-History_in_140_characters_Craig.pdf

Current activity: I use this as to anchor week 2 of H213 The Black Death, to engage students in the variety of ways to read primary sources. Readers can view archives for either the Tweets generated by students in Spring 2018 H213 The Black Death or students in the Spring 2020 H213 The Black Death. The PHP code is available for download and perusal (without some of the libraries that power database calls and other basic programmatic functions).

-

Breaking Modern Context with Modern Technology

Modern conceptions of the medieval past are often rural and dirty, in part because we import assumptions about modernity into our study of history. I designed this study around the use of smartphone GPS and computer simulations, using modern technology to expose our modern context and make it easier for students to position primary sources in their proper historical context.

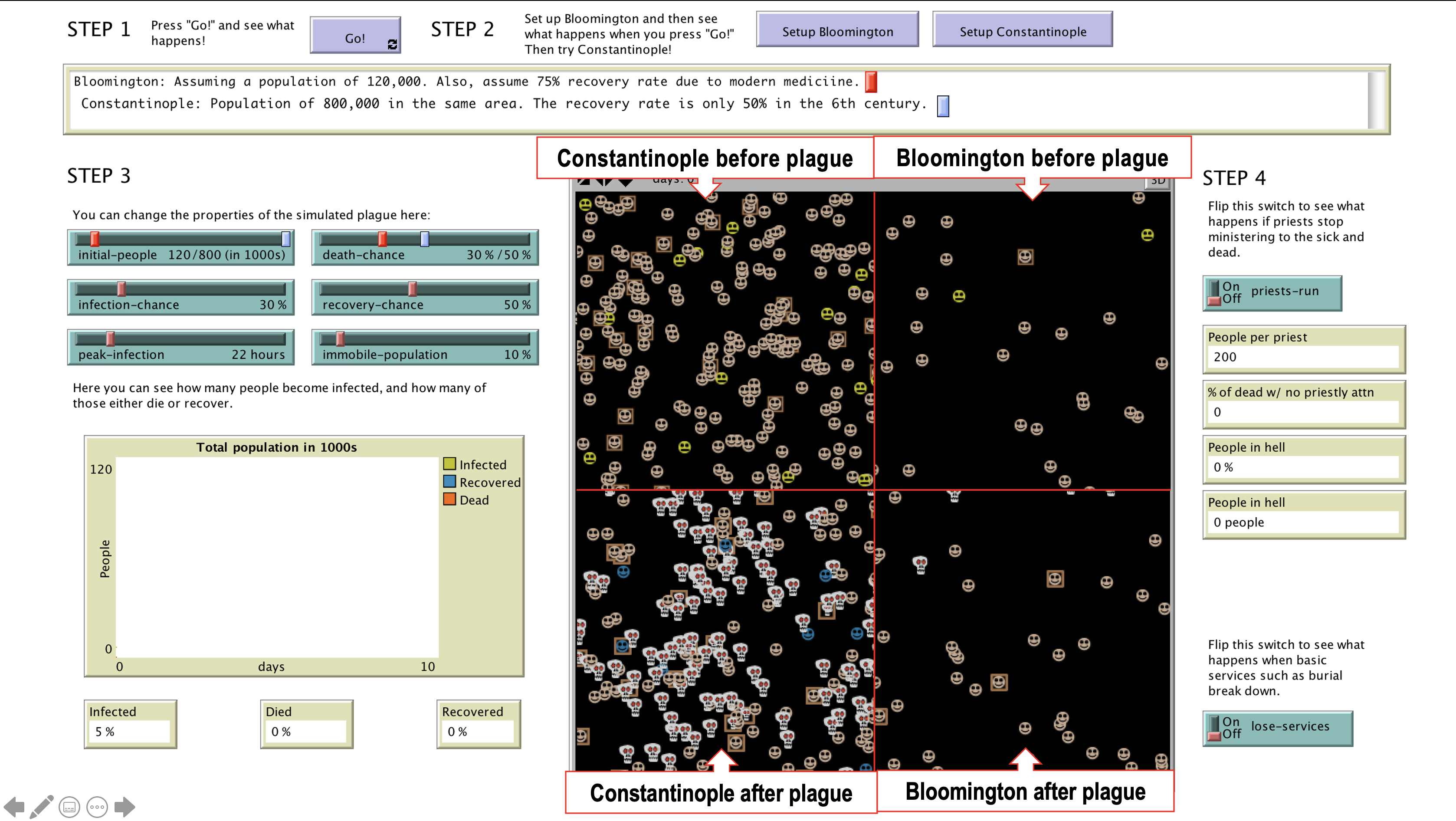

This empirical educational research study extends my work on using modern tools to familiarize students with historical context into the more complex technical world of mapping. Our goal was to expose students’ present context by making that context visible to them, help them tie that present context to the past, and then connect their contextual understanding back to the primary sources about plague spread. To transfer student understanding of modern context into a historical context, we took advantage of the fact that Bloomington is approximately the same square mileage as the sixth-century walls of Constantinople, but with a dramatically different population density (120,000 people vs. an estimated 500,000 residents, respectively). We made the similarities and differences between their modern context and Constantinople explicit by using the same mapping and epidemiology tools to explore the geography described in primary sources from sixth-century Constantinople."

In Spring of 2018, several adaptations to simulation that added Siena, Italy, and a geospatial reference in the simulation itself expanded the simulation’s value as a classroom tool: it served as a first-day introduction to H213 The Black Death, as a way to explore the urban density of Constantinople in week 4, in week 6 as a way to explore the variety of Christianities in the millenium that is the Middle Ages during our transition from Constantinople in 542 C.E. to the 1348 plague , and in week 10 as an introduction to the transition from medieval to early modern as we explored plague outbreaks in early Renaissance Italian city states.

Project Role: Principal Investigator, project manager and software co-designer. Managed team of 6 collaborators to adapt software, to develop long-term research questions, write grants and publications, develop tool features, and design in-class activities.

Publications:

-Kalani Craig, Charlie Mahoney, Joshua Danish, Correcting for Presentism in Student Reading of Historical Accounts Through Digital-History Methodologies", in AERA 2017 Annual Meeting Conference Proceedings , San Antonio, TX, April 26-May 1, 2017. Full manuscript or the official conference proceeding listing

Current activity: The simulation, in one form or another (often with adaptations to meet new teaching goals) makes an appearance each time I teach H213 The Black Death (with Spring 2020 as the most recent example). The simulation is also a central part of one portion of my public-engagement work, in which I talk about how we can use modern technology to explore the past. It’s been used in graduate digital history courses at other universities as part of a digital-history pedagogy reading. The simulation was particularly relevant for a public talk as part of the Quarantine(d) Conversations Zoom-panel series in Spring of 2020. The full activity, including the simulation, is available for download and use at http://www.kalanicraig.com/theblackdeath/.

-

Problem-Based Learning to Support History Argumentation

Like many humanists, I think students should master argumentative writing; the one-on-one source analysis and writing coaching necessary to learn how to craft a thesis from available evidence (rather than drafting a thesis and then hoping the evidence fits) can be difficult in a large survey course, however. In this study, I worked with a learning-sciences and IST graduate course to create a guided single-class-session whiteboard activity that helped students and instructors alike see how students were gathering and organizing evidence from primary sources and using that to construct a thesis statement.

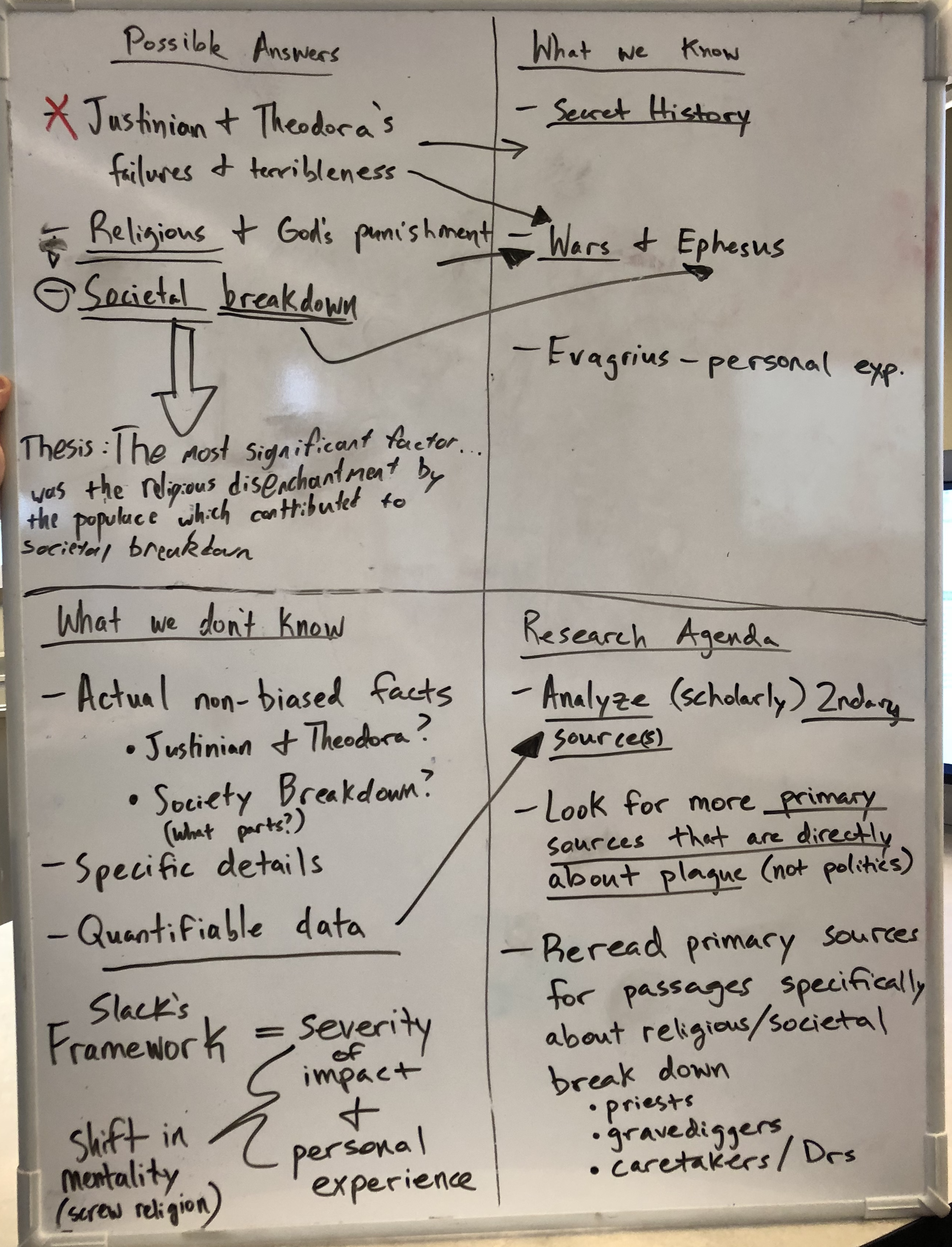

Single-session activities designed to help students tackle primary-source analysis, secondary-source comprehension and historical context are all important, but the ultimate goal in a history classroom is to wield all of those skills in service of a long-form historical argument. A variety of mistakes happen at various stages in the student writing process, which can make specific mistakes hard to diagnose and result in too-late intervention. Problem Based Learning provides a quadrant structure that supports organized brainstorming, a process often used during training for medical students who need to find the best treatment given a list of current symptoms and competing diagnoses.

Adapted for history, this same PBL quadrant exercise can be used early in the writing process to provide students and instructors with a platform to communicate the development of a thesis and its evidence. The quadrant divides a white board or large poster paper into 4 parts, and students or small student groups fill out each of the 4 parts, in stages, during a class session. The instructor can easily see each of the thesis statements students have put forward (“Possible Answers”), what evidence students have available (“What We Know”), where there are gaps in student knowledge (“What We Don’t Know”) and what research students think might help fill those gaps (“Research Agenda”). More importantly, instructors can prompt students to draw connections between each of the quadrants so students can clearly see which pieces of evidence tie to which thesis statements. The process gives students a systematic process they can use to rule out thesis statements they like but can’t support with good evidence, and it allows instructors to clearly see and help guide student critical-thinking processes that are normally hidden. These PBL quadrants, from Spring 2018 H213 Black Death Class, show students’ first experience with the PBL process.

Table 2

Table 9 Research on PBL in a large history classroom is an innovative contribution to the world of educational research for two reasons: first, PBL is generally used with fewer than 15 students at a time, and the value of PBL in support of historical thinking has never been studied. In its current iteration, we’re using PBL for 96 students at a time with a specific focus on historical argumentation.

Project Role: Principal Investigator, activity designer Designed in-class activities, collaborated with graduate-course instructor and 10 educational-research Ph.Ds, led history-learning portion of the writing process.

Publications:

- Haesol Bae, Kalani Craig, Fangli Xia, Yuxin Chen, Cindy Hmelo-Silver, “Developing Historical Thinking in Large Lecture Classrooms Through PBL Inquiry Supported with Synergistic Scaffolding”, in Rethinking Learning in the Digital Age: Making the Learning Sciences Count, 13th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2018, pp. 1438-1440 ( June 2018 )

- Haesol Bae, Kalani Craig, Cindy Hmelo-Silver, Fangli Xia, Yuxin Chen, “Developing Historical Thinking in Large Lecture Classrooms Through PBL Inquiry Supported with Synergistic Scaffolding”, third round of submissions under review as of November 2019 at Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning (as second author).

Current activity: I use this in both large and small history courses every semester at the beginning of each student project, so that I can model how to use evidence to draft a thesis (rather than fitting evidence to an already-written thesis) using the activity process I refined for the purposes of this PBL study.

Service in Teaching: Digital-methods training & consulting

My teaching most often overlaps with service in the form of professional-development instruction and consulting for faculty and graduate students who have begun to explore digital methods in their own research and in their classrooms. I incorporate lessons from my tool building and digital-history pedagogy research into invited and research-conference talks, structured workshops, and consulting practices. These events help other faculty and graduate students hone their digital-methods approaches in disciplinary-specific ways. By contributing professional-development and digital-humanities training opportunities, I can help bring perspectives on developing digital-methods expertise from the Department of History and IDAH to a broader audience outside of IU.

Digital-methods invited talks and research presentations

Invited talks often draw equally on my administrative and professional-development skills in digital humanities and my digital-methods research skills. As my interest and expertise in professional development in digital humanities has grown, I’ve also begun to provide digital-methods capacity-building consulting as part of an invited-talk visit. Two international invited talks characteristic of this change since 2015 are the highlight of this part of the dossier, which includes 12 invited talks and more than 20 research presentations (6 of which were full-length papers for peer-reviewed conference proceedings).

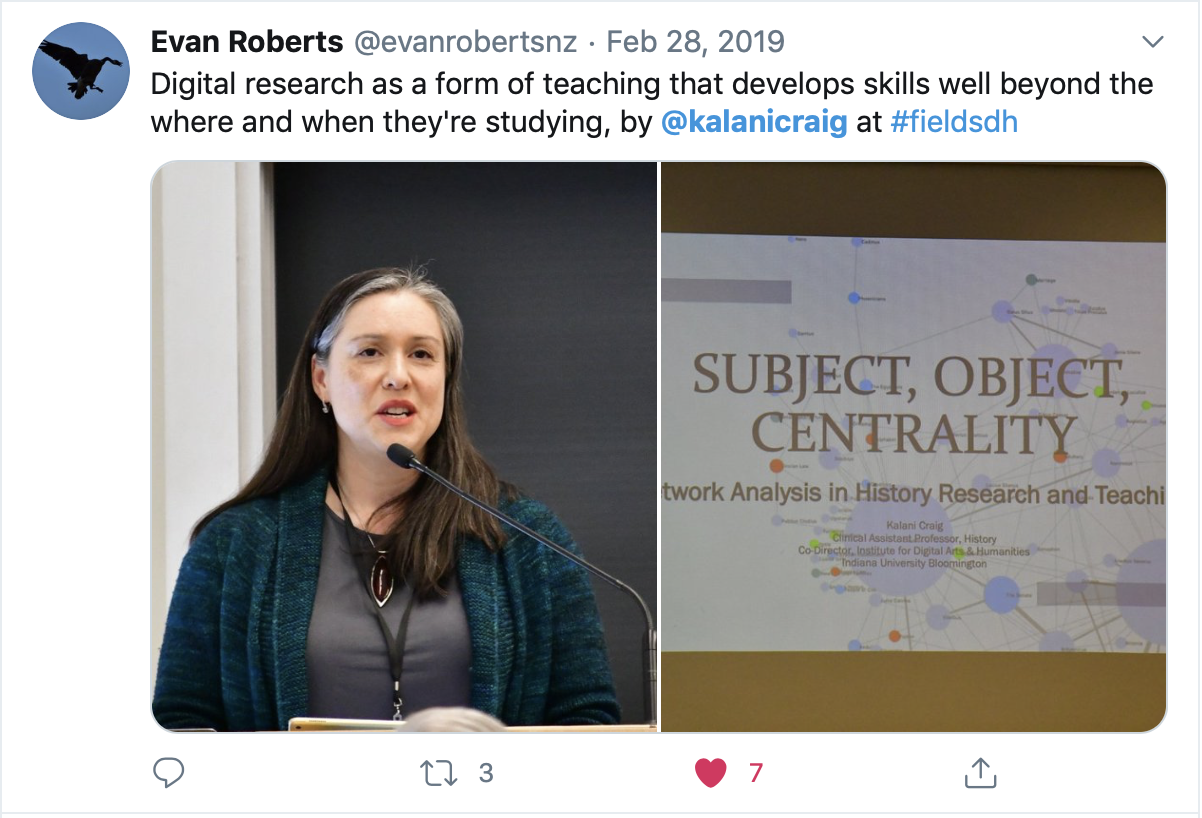

My first international invited research talk, to the Chinese University of Hong Kong for their “Translation Studies in/and the Digital Humanities” conference, was a fairly traditional research-oriented talk on multi-lingual topic modeling as one approach to computational text analysis. Audience interest led to an impromptu workshop teaching topic modeling; this request came as I was first thinking about the integration of digital-methods teaching with my work at IDAH, and the experience teaching topic modeling overseas on a whim shaped much of my thinking about the work I’ve done since. The second international invited talk–“Subject, Object, Centrality: Network Analysis in History Research and Teaching” for a 2019 “Workshop on Quantitative Analysis and the Digital Turn in Historical Studies” at The Fields Institute in Toronto–reflects that shift in its explicit focus on how my research in undergraduate classrooms shapes and is shaped by my research and tool-building contributions to the digital-humanities community.

As my interest in professional development in digital humanities has grown, I’ve also begun to provide digital-methods capacity-building consulting. Two institutions (Ball State University and Baylor University) have invited me to their campus for talks and workshops designed to develop their local digital-humanities teaching and research expertise, and these visits also included both impromptu and scheduled meetings with administrators about funding models, graduate training and faculty-research program design. IDAH also hosted the administrators of Saint Louis University’s Center for Digital Humanities to the same end; their director and a post-doc shadowed Michelle and me in Fall of 2019 for a two-day exploration of our model for developing digital-humanities projects from nascency to publication.

In addition to the AHA and to larger-scale invited talks with integrated workshops, I have done a number of smaller invited talks and workshops beyond the walls of IU, including a virtual talk that was streamed nationwide live in April 2016 for The Association for Jewish Studies and the Association for Slavic, East European, & Eurasian Studies, which has been viewed 340 times since. A full-day workshop for DePaul’s history faculty in 2017, entitled “Crafting a Digital Syllabus”, brought 12 faculty from DePaul together to look at the basics of digital methods in a lunchtime brown-bag talk, which was followed by a 3-hour workshop on crafting syllabi for digital-history courses and digitally-inflected topics courses. I also provided an introduction to humanities for Case Western’s Big Data working group in 2016.

Research-methods talks at national and international conferences—the AHA’s Annual Meeting, the International Congress on Medieval Studies, and the Association for Computing and the Humanities—follow this same trajectory and are representative of a number of other local or regional talks on digital methods.

Digital-methods workshops

I have personally led more than thirty workshops ranging in size from 5 to 150 people, many of which focus on best practices for getting started in digital humanities. These form the core of my service-in-teaching work. Organization of the Getting Started in Digital History Workshop for the American Historical Association’s annual meeting from 2013-2019 (AHA GSDH) is particularly representative of workshops that have helped raise IU’s profile in digital-humanities expertise outside the bounds of IU’s campus.

In 2012, Seth Denbo, the former Director of Scholarly Communication at the AHA, approached me to help plan the first AHA GSDH workshop and it’s been a staple of the annual meeting’s digital offerings since then. I organized the 2014 workshop individually, and have since collaborated with Rebecca Wingo, now Director of Public History at University of Cincinnati. Attendance increased each year, from 75 initially to nearly 150 in 2019. All told, the workshop has provided training for approximately 625 attendees, 10% of whom have attended at least a second, and sometimes a third workshop. The plenary presentation in each year of the workshop has been my responsibility (shared with Seth Denbo or Rebecca Wingo, depending on the year). In 2014, 2015 and 2017, I also personally offered one of the training sessions embedded in the GSDH workshop: introductory mapping to approximately 35 people, an intermediate workshop on historical evidence as data to 14 people, and a text analysis workshop to 10 people. The text-analysis workshop attendees included a former head of Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Director of the Washington Office at American Academy of Arts and Sciences, who used the text-analysis workshop to underpin an NEH grant. Each AHA GSDH workshop is also accompanied by an AHA-sponsored Digital Drop-In session. Conference attendees bring an impromptu question to the session organzer and are triaged on a first-come-first-serve basis for 15-minute short consults with the digital-history experts in attendance, and I offer my consulting expertise each year (right); hearing about the projects from other AHA members at each year’s Digital Drop-In session is a highlight of my AHA conference-going experience. Finally, the workshop spawned an article for AHA’s Perspectives on History magazine entitled “What Do Digital Historians Want? Lessons from the AHA’s Digital History Workshop”, coauthored with Rebecca Wingo.

Workshops done on IU’s campus constitute another major arena of digital-methods outreach that takes service form but is teaching-oriented. These workshops are dominated by two series sponsored by IDAH, in which I participated first as a member of the Department of History and then in official capacity as IDAH’s Co-Director. Each year since 2017, IDAH has hosted a Choosing a Digital Method series, which includes workshops that shift the language around digital methods away from the tools and approaches and into the specific research questions that digital methods can support. With Michelle Dalmau, I have restructured IDAH’s spring workshop series to accommodate the changing trends in digital humanities by crafting a workshop series around matching the traditional work of humanities evidence gathering with the systematic structuring of data that drives maps, text analysis and networks. In total, I personally delivered 12 of the 20 workshops we have presented over the course of 3 years. These IDAH workshops have drawn in-person audiences of more than 300 people since Fall 2017, and the talks continue to influence budding digital humanists as part of the online resources IDAH includes in its web-based digital-methods training section.

Smaller-scale workshops across a variety of subjects—an introduction to Laser Cutting for the School of Education’s Make Innovate Learn Lab makerspace, three digital-methods workshops for the Department of History’s Historical Teaching and Practice series, and a single-summer-teaching-activity pedagogy workshop for the History Graduate Student Association—demonstrate the breadth of topics these workshops have covered.

Digital-methods research and teaching consults

Rounding out the service-in-teaching work is a regular practice in digital-methods and digital-pedagogy consulting. Some of these teaching consults take the form of publications, like a teaching-activity review of a digital-history platform, the Making of Charlemagne’s Europe, for the American Historical Association’s Perspectives on History magazine.

At IU, that has had several iterations. In 2015 and 2016, these consults with individual faculty and graduate students were largely limited to faculty and graduate students in the Department of History looking for new approaches to their research and new activities to bring into their classrooms.

In 2017, on appointment to IDAH, I worked with Michelle Dalmau to incorporate practices from our two consulting models (hers from the digital-collections-services consulting that began in 2014) into a model that acknowledged the need to combine disciplinary research questions with digitization and digital-archive considerations from the very beginning of every digital project. Since then, IDAH has offered more than 300 digital-methods consults on this model, including almost 70 digital-pedagogy consults; with each of these consults comes the opportunity learn something new.

Across all of these iterations, formal and informal consults with faculty, graduate students and digital-methods consults with a number of history faculty have benefited the department at large. Digital-methods consults with Arlene Diaz, Kon Dierks, Ellen Wu, Jason McGraw, Michelle Moyd and others have resulted in both internal and external funding for traditional articles and monographs as well as for digital projects. These include a book project that tackles the historiography of American colonialism in the Cuban War of Independence, a social-media text analysis project that tracks Asian-American responses to affirmative action in academic admissions, a History Harvest focused on IUB identities, a spatial-history appendix to a book project on Jewish choral music in the nineteenth century, and a network of 16th century Venetian musicians.

Formal classroom consults take these digital methods and repurpose them in service of teaching humanities analysis at the undergraduate and graduate levels. My goal for classroom interventions has been twofold: for faculty and graduate students, I see these classroom visits as demonstrations of potential that lead to more substantive digital-methods research consultations. For undergraduates, these classroom interventions are designed to provide thoughtful active-learning lesson plans that anchor students’ experiences as lifelong smartphone users in the humanistic disciplines. Since 2015, in-classroom visits for history faculty have included: Colin Elliott, Jonathan Schlesinger, Pedro Machado, Jason McGraw, Maria Bucur, Roberta Pergher, Arlene Diaz, Ke Chin Hsia, Michelle Moyd, Cara Caddoo, and Fei Hsien Wang, with whom I worked to build this mid-1960s Chinese mango shrine. In addition to these in-classroom visits, I’ve provided shorter out-of-classroom digital-pedagogy consulting on timelines for Leah Shopkow, museum exhibits for Eric Sandweiss in his role as a member of the steering committee on IU’s Environmental Grand Challenges grant, games in history learning for Eric Robinson, and formal and informal Canvas support for more than a dozen other faculty members (including Rob Schneider, Danny James, Jeff Gould, Ben Eklof, and Tatiana Saburova).

During the frantic COVID-19 transition to remote learning in March and April of 2020, I also helped the Department of History restructure its teaching offerings, both in individual Zoom consults and by way of a public online teaching-resource web page that incorporated many of the best practices from IU’s CITL, from IU’s online-course-design faculty, from my own research and experience, and from the outcome of history-department-specific COVID-19 consults. As part of building this web-based guide to remote teaching, I explored the range of options available to faculty, narrowed down those that were likeliest to result in readily approachable classroom practices for faculty used to in-person instruction, and then produced video guides for many of the tools faculty were most likely to need under the circumstances. Instructional consultants at IU’s Center for Innovative Teaching & Learning (CITL) used resources from the page I created in portions of their campus-wide remote-teaching support, and I used it as the basis for my contribution to a CITL-sponsored Zoom panel entitled “The Affordances and Constraints of Using Zoom in Synchronous and Asynchronous Teaching”, which had 75 attendees from all across IUB’s campus. Between its launch on March 8 and May 20, the page was viewed 175 times by more than 150 viewers.

Teaching

When I began teaching history, my primary goal was to help students understand the skills involved in historical practice as a way to accommodate, synthesize and intelligently use the ever-increasing volume of communication they deal with, both personally and professionally. The high-level critical thinking and analysis we employ to deconstruct, contextualize and synthesize primary and secondary sources can be used equally well in support of a historical argument, to analyze a voting choice, or to justify an important business decision. In an early course evaluation, though, a student expressed disappointment that my assignments were too focused on supporting an argument with evidence. While I was thrilled that the student felt comfortable using a newly learned historian’s tool kit, I was also reminded that historical practice sometimes overshadows the wonder that comes with exploring a world full of new names, dates, and places. My ongoing teaching challenge is thus to both demonstrate the utility of historical practice and simultaneously communicate my awe of and enthusiasm for exploring the past.

Curriculum development

Curriculum development at the campus level has occupied a portion of my service duties, at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Each of these curriculum-development efforts has centered on the ways in which humanities learning can be augmented by digital methods at the same time that we encourage students to question the assumptions and algorithms built into those digital methods.

The Digital Arts and Humanities PhD Certificate and Minor have been part of my service to IU since before my official appointment to history. In 2014, the committee to develop a certificate program convened without a historian, and I sought permission from then-chair Eric Sandweiss to represent history’s needs. The certificate and minor program cleared the IU systemwide approval process in mid-2017, and on my appointment as IDAH’s co-director in August of 2017, I took on the task of developing the curricular and administrative infrastructure necessary to launch the program. That included the recruiting and convening of a curriculum committee to oversee and advise students in the program, as well as the development, submission and teaching of new courses to meet the program requirements. At the end of the 2017-2018 year, its first year in existence, we awarded the certificate to 3 people (including the producer IU’s first born-digital dissertation in the College of Arts & Sciences, right, and 1 history graduate student) and the minor to another 3 (1 history graduate student), and the program currently has 8 students at various stages of progress to degree, with 5 of them matriculating to the minor or certificate program in 2019-2020. As part of IDAH program-building efforts under my purview, the IDAH staff visits a number graduate student orientation programs each fall–I presented at 5 personally in 2019 alone–and we have developed outreach programs to DGSs and chairs across a variety of schools and departments to bring more students into the certificate/minor program. Advising and peer-review of students in the certificate and minor program is my responsibility as the disciplinary specialist among IDAH’s co-directors.

The College is also developing several undergraduate programs that center technical and scientific practice in the critical lens of humanities interpretation. I was initially invited to join a working group tasked with developing a humanities research track for first-year students; now called ASURE, the program has been on offer for College direct admits since Fall of 2018 and includes a fall-semester introductory course, which I chaired a subcommittee to develop, and a spring-semester hands-on research course, for which I developed and taught A200 Digital Public History. These curricular-development efforts also include a committee seat on the College’s Undergrad Computing Task Force and its subsequent Committee on Undergraduate Computing in the College, which resulted in a Spring 2020 report that lays out concrete curricular programming, in several tracks, to prepare students for disciplinary-specific use of technology in service of their chosen humanities majors. In the long term, both programs include efforts to bring students from the University’s professional schools to courses in the College and the Department of History.

Course development

Each of the courses developed for IU’s Department of History is either oriented toward teaching digital methods for historical argument or is digitally inflected and uses digital methods where appropriate in a topics course. As I develop or redevelop a course, I keep a single guiding principle in mind: history’s systematic approach to interpreting documents in service of rebuilding historical context and exploring change and continuity over time. While a professional historian can and should push the boundaries of that system in order to create new knowledge, our students often need scaffolding before they can be asked to use all of these skills together. I want to provide enough systematic training for students to do history on their own—to systematically assess documents, take historical perspective, build context, and integrate primary and secondary sources—while still giving the advanced students who do understand the basics of a systematic approach to history enough room to push those boundaries.

This principle has resulted in two practical goals for students: a learned independence that fosters willingness to make mistakes, which in turn supports the construction of open-ended historical argumentation. My emphasis on classroom-based activities, then, is designed to give students access to expert guidance in class, so that guidance can shape their reading and research outside of class. This approach is reflected in student evaluations. Across all classes, evaluations consistently note the emphasis on learning in class, on having high expectations for student work, and on instructor support for in-class projects. Clarity of expectations has been less consistent, a rating which I’m willing to accept for the sake of encouraging students to set their own expectations, and which I believe is more prevalent in my digital history courses, which require undergraduates to undertake an initially scary digital-history research project from the ground up in a single semester (see H301 below). To address this gap, I start semester by clearly communicating my preference for learning over grading, which I have supported in all of my classrooms with generous grading policies that encourage mistakes and revisions.

In all of these courses, I use what I’ve affectionately nicknamed a “Living Syllabus”, documented by a 2015 CITL faculty spotlight, that replaces the static syllabus with several pages in our learning-management system, Canvas, and uses cloud storage to archive and organize the work students do in class. The end result is a body of resources collaboratively built by students in the class, with my guidance, that brings all of their work over the course of the semester together into an archive. I start with individual Canvas assignments for each reading assignment and due dates easily accessible from the Canvas calendar. I then use the Canvas web-pages feature to build a course home page that changes, course-session by course-session, linking to the day’s reading, any resources students might need for in-class activities that day, and to the specific location in our cloud storage where I’d like them to save their work.

The syllabi in this packet were originally structured as interactive web sites on this model to support daily active-learning engagement. I’ve provided a brief 3-minute tour of one course to model how students interact with the syllabus to engage in in-class inquiry, team-based argumentation and writing, and the creation of an activity archive built over the course of the semester. While H213 The Black Death and H301 Digital History are both well developed courses with several versions of each course in place, I’ve chosen to feature B200 Medieval Saints and Sinners as the case study for the syllabus walkthrough and the video demo of my teaching practice. As a new course prep that hasn’t been repeated since it’s initial offering, it provides a good example of how I bring all of the different elements of my appointment into conversation. It’s 2 years old, so I had a well developed digital history and Black Death course at the undergraduate level to draw on; at the same time, because it’s now 2 years old, I can point to specific elements of this class that made it into the digital history courses that took place in the two following semesters, and I’m using the grading scheme from Saints and Sinners in a redeveloped Black Death course for the Fall 2020.

From small to large classrooms, from teaching to research and back again, with an eye to assessing each course activity at a small scale, the “Living Syllabus” is emblematic on a small scale of how I look at the evolving framework of my teaching from semester to semester on a larger scale, so that even well-developed courses get a critical look each time I teach them.

- View a list of courses taught by chronological order

- View a set of sample course materials and learning outcomes from B200

-

H213 The Black Death

This introductory survey---for which enrollment is dominated by students in natural and health sciences, business, and informatics--tackles the history of cultural and social responses to outbreaks of bubonic plague. The course is structured in roughly 5-week units around 3 pandemics (the Mediterranean in the 6th and 14th centuries and the Pacific Rim in 1900), and we explore these pandemics using a team-based active-learning agenda that augments primary-source analysis and lit-review construction with computer simulations and virtual reality, computational text and spatial analysis, and public-engagement approaches to presenting historical arguments.

H213 The Black Death has filled each term, with an increase from 75 seats in Fall 2015 to 96 seats in Fall 2016, Spring 2018, and Spring 2020. It has undergone three major course revisions and an additional revision to address the remote-teaching needs of the Spring 2020 COVID-19 semester. It is home to three of my educational-research or SoTL studies. Its current iteration, in IU’s largest active learning classroom, includes virtual-reality encounters with cathedrals built in the mid-14th century designed to highlight the story-telling nature of the discipline of history, several encounters with systematic argumentation to highlight the importance of thoughtful accurate use of evidence, and now in its online form, a network-analysis encounter with Net.Create that was redesigned to help students see their individual work at home as part of a larger classroom-wide project without requiring synchronous attendance or high-bandwidth, high-computing-need environments.

The Fall 2015 version of H213 introduced a simple version of the Black Death mapping and simulation exercise. Student evaluations from Fall 2015 prompted more focus on the specific history-learning goals supported by each digital method, but the primary issue for students was with the classroom space itself. In Fall of 2016, thanks to my work as a Mosaic Fellow , the course moved to Student Building 015, a classroom with 16 computer-equipped tables of 6 students each. This necessitated a complete revision of the course (syllabus & evaluations ), including a major reading revision that added more late-antique primary sources and moved more quickly from the 1348 outbreak to the 1900 outbreak, a major shift in assignment structure from individual to group-based work, and the introduction of problem-based learning quadrants (see above). In Spring 2018, I did a major revision of the non-assignment activities, with two specific goals in mind: to help students negotiate the gap between fun history and serious history, and to better train students to find and assess the significance of secondary sources. Two major digital-history-activity changes support these goals. First, a VR encounter with Siena, Italy, is tied to a second encounter with an epidemiology simulation, in order to tie virtual reality and the embodied experience of public and popular history to the evidentiary basis of academic history. Second, refinements to Net.Create and its integration into the three-week encounter with Plague and Fire, together with several BOX-centered JSTOR and OneSearch activities, supported students in integrating secondary source material more effectively into their historical tool kit.

In Spring of 2020, an offering of H213 that was initially intended to be a minimally-revised version of the Spring 2018 course was instead fully revised to meet distance-learning needs for the COVID-19 outbreak. After much consideration, I reshaped the entire last 4 weeks of the semester around Net.Create as a collaborative note-taking tool, a task that included adding “citation” buttons to the interface, giving students more control over both whole-class and small-group interactions in Net.Create, and providing more explicit instruction around using Net.Create as a reading guide. The resulting student network was spectacular. In very basic assessment terms, Net.Create offered a solution to one of the perennial issues I struggle with in training future historians: engagement with citations that demonstrate their understanding of the back-and-forth conversation in which historians engage. A mere 23 of nearly 350 historical interactions entered by the students lacked citations, which is impressive considering that we would normally see similar numbers in an in-person class where we had the freedom to circulate and re-emphasize citation practices. More importantly, they understood what was in the text: 90% of the entries included both accurate identification of the historical actors and thoughtful historical context that helped explain those actors’ behaviors.

Course syllabi:

-

H585 History in the Digital Age

This graduate colloquium is designed to provide a basic foundation for graduate students who need to acquire the theoretical and technical skills and the familiarity the rapid pace of historical scholarship necessary to practice digital history.

This course was designed to provide a basic foundation for graduate students who need to acquire the theoretical and technical skills necessary to practice digital history. Regardless of their initial skillset with technology or digital-methods theory, every graduate student from both the Spring 2015 and 2016 iterations of H585 has integrated digital history into their work. Three of the six students will receive the Digital Arts & Humanities Certificate or Minor. Four of the six have integrated digital history into their dissertations (3 history dissertations, 1 informatics dissertation). Another integrated digital history into PhD applications at schools outside of IU. The sixth student parlayed the programming with which she became comfortable during our digital-history semester into a job after leaving IU’s history graduate program, and then and as part of a successful law school application.

Many students from the Fall 2019 course have taken similar paths in the limited time since that course’s completion. One used the course to workshop a grant that was subsequently successful. Another workshopped a crowd-sourced platform designed to be used in art-historical cataloging for the Eskenazi Museum of Art at IU. A third successfully repurposed their digital project to win a Library of Congress research grant. A fourth matriculated to the Digital Arts and Humanities minor that I oversee at IDAH. Finally, a fifth student was hired as a digital-scholarship librarian partially on the strength of their digital project. That said, the Fall 2019 version of the course was dual-enrolled with an undergraduate course, and that created some issues. While this teaching arrangement succeeded in a prior term (Spring 2017) with 2 graduate students and 12 undergraduates, a registrar-cap issue brought 9 graduate students into the classroom with 16 undergraduates. The size of both classes made the teaching arrangement less manageable, and I hope to address this in future iterations of the course.

Course syllabi:

-

H301/J300 Digital History and A200 Digital Public History

These mid-level research-oriented courses help undergraduates explore the research methods and technologies that frame three approaches to digital history: computational network analysis, text analysis, and spatial analysis. While separate in both preparation and staging, the development and subsequent revisions in each of these courses have influenced how I teach the others, so I'm clustering them here to make the longitudinal structure more visible. All of these courses emphasize writing. The H301 version focuses on documenting digital-methods research and analysis generally; the J300 version adds a university minimum for words written (5000) and words revised (3000); the A200 version privileges writing in clear, straightforward language for the public. The most recent version of the H301 course draws on both the J300 writing requirements and the A200 dedication to a History Harvest, a public engagement project that gives the students a public-history archive-building experience from start to finish plus a full-length digital-history research project built on those public-history archives.

While separate in both preparation and staging, the development and subsequent revisions in each of these courses have influenced how I teach the others, so I’m clustering them here to make the longitudinal structure more visible. The first course in the cluster, H301, had a more open structure that—while it still included carefully staged bibliographies, project proposals and digital history components—was more suited to graduate work or for students with experience in either history or informatics. For those students, the course was particularly successful, as evidenced by one student who recently applied to the Digital Humanities specialty track in Information Library Sciences. Additionally, in-person comments from students across several semesters of various iterations of the course noted that it was the first time they had ever truly enjoyed a college course (one of them a graduating senior), because of the combined challenge of digital methods and a research topic of their own choosing.

At the same time, the H301 structure was less successful for students whose interests were less oriented toward history or technology or both. The shift in evaluations from H301 to J300, which results from changes I made in response to a negative, though very constructive, comment demonstrates improvement in student evaluations that is both encouraging and still leaves room for more improvement. In particular, I refocused the J300 version of undergraduate Digital History on a two-part project with more specific guidelines that developed a traditional history research project in the first 8 weeks of the class and a digital-history enactment of that project in the second 8 weeks.

The third and fourth versions of Digital History share a focus on the collection, analysis and presentation of a digital public-history project focused on the ephemera the IU community bring to campus as part of their own history, done in the tradition of a History Harvest. Spring 2019 A200 Digital Public History asked first-year students who enrolled in a research-experience program to explore best practices and ethics for public-history engagement and then plan and execute a small-scale first-year-research-experience History Harvest with their fellow IU first-year-student cohort. The objects they collected during their History Harvest then became the foundation for a digital exhibit, and an in-person exhibit in the lobby of IU’s University Archives (right).

The standout, Fall 2019 H301, is largely the result of several semesters worth of tinkering with these various models. These students worked with the best features of the public-history project planning done by A200 students, enacted a History Harvest on a larger scale, with the whole IU campus and two research-center partners (IDAH and CRRES), and then used digital methods from the original H301 course like network analysis, text analysis, and geospatial history to analyze and write a history of IU’s identity through those objects. The evaluations suggest that the public engagement and service learning component of the course provided a concrete anchor in real-life experience that helped them make more sense of the more abstract digital components of the research project. The network groups in particular produced a spectacular exhibit for their portion of the Identity Through Objects History Harvest; not only did they produce individual projects, they combined these projects into a single integrated essay that drew on the best of both endeavors.

Course syllabi:

-

B200 Medieval Saints and Sinners

This medieval-history survey course focused a medieval survey narrative around the (artificial) binary of good vs evil and structured its historical thinking focus by asking students to dive into what periodization means in historiography. Each week, students built timeline entries to anchor their reading, and at the end of the semester, I guided them through a 4-week exercise in historiography in which each student used all of the timeline entries generated by the entire class to argue for their own periodization of the Middle Ages.

This topics course focused a medieval survey narrative around the (artificial) binary of good vs evil and structured its historical thinking focus by asking students to dive into what periodization means in historiography. Each week, we encountered two primary figures—a “saint” and a “sinner”—and used them to explore the complex social, political and cultural interactions of the Mediterranean world between 500 and 1500. The course is structured with a particular eye to using and breaking pop-culture versions of “medieval”. As an example, the first week muddies the waters by presenting St. Augustine as both saint and sinner, and introduced students to a medieval world populated by a diverse cast of historical figures, not just the blond blue-eyed Vikings that show up on the history channel and that were central to a debate in the medieval academic world that was raging in Fall of 2018 (and continues to be a concern) about the co-optation of “medieval” for racist purposes.