15 May 2020 update: My team and I built a user-friendly computational network analysis tool that is a nice add-on to this exercise. Net.Create lets many students add to a network simultaneously and see both its underlying data and a live visualization each time someone adds something.

31 Jan 2017 update: A full article has been published as “Analog Tools in Digital History Classrooms: An Activity-Theory Case Study of Learning Opportunities in Digital Humanities”

If you haven’t read the Analog Tools Background and Assumptions post already, pop in and have a look around before reading this.

I first envisioned this lesson plan after reading Mac Carron and Kenna’s “Universal properties of mythological networks” and some of the critical responses to the article (notably Carrier’s “Bad Science Proves Demigods Exist!” and the Humanities Hackathon post at Quomodocumque).

Learning Outcome Goals for Students

- To become familiar with the idea of using a network to analyze a historical or literary document.

- To understand that visual representations have built-in arguments, whether we’re aware of them or not.

- To think about the implications of the Iliad as a primary source, in both its fictional form and its potential as having some basis in historical fact. We read Herodotus early in the semester, and this goal is oriented toward a synthesis of the two texts.

- To get more exposure to the text at large before they chose which books to close-read for days 3 and 4 of the Iliad unit.

The Activity

In the first few minutes of class we talked about the three basic characteristics of a “real” social network that Mac Carron and Kenna lay out: assortativity, balanced/triadic and ease of destructibility. We looked at some sample social-network visualizations–among them, my Facebook network visualized in gephi–so they could see how each of the three characteristics might look when represented in a network graph. Finally, we talked about the concepts of network node and node distance.

Students then worked on a draft of the network in small groups of 7-8 and used that draft to decide whether they thought the Iliad met one or more (or none) of the three basic network characteristics we’d talked about. Their deliverable as a group was a final draft of their network visualization drawn on the chalkboard, and their goal was to get the most classmates to correctly guess which three characteristics their network visualization represented.

The Results

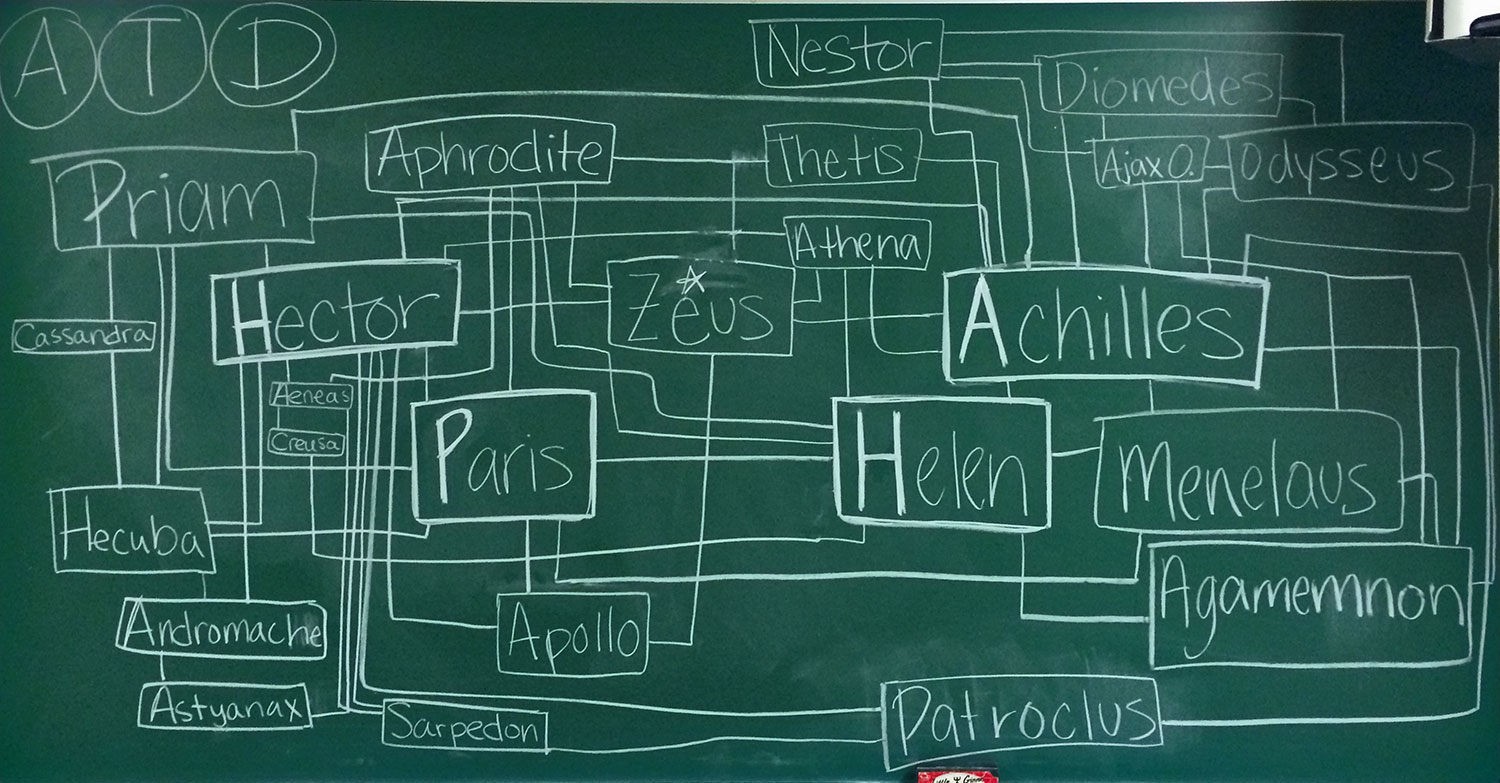

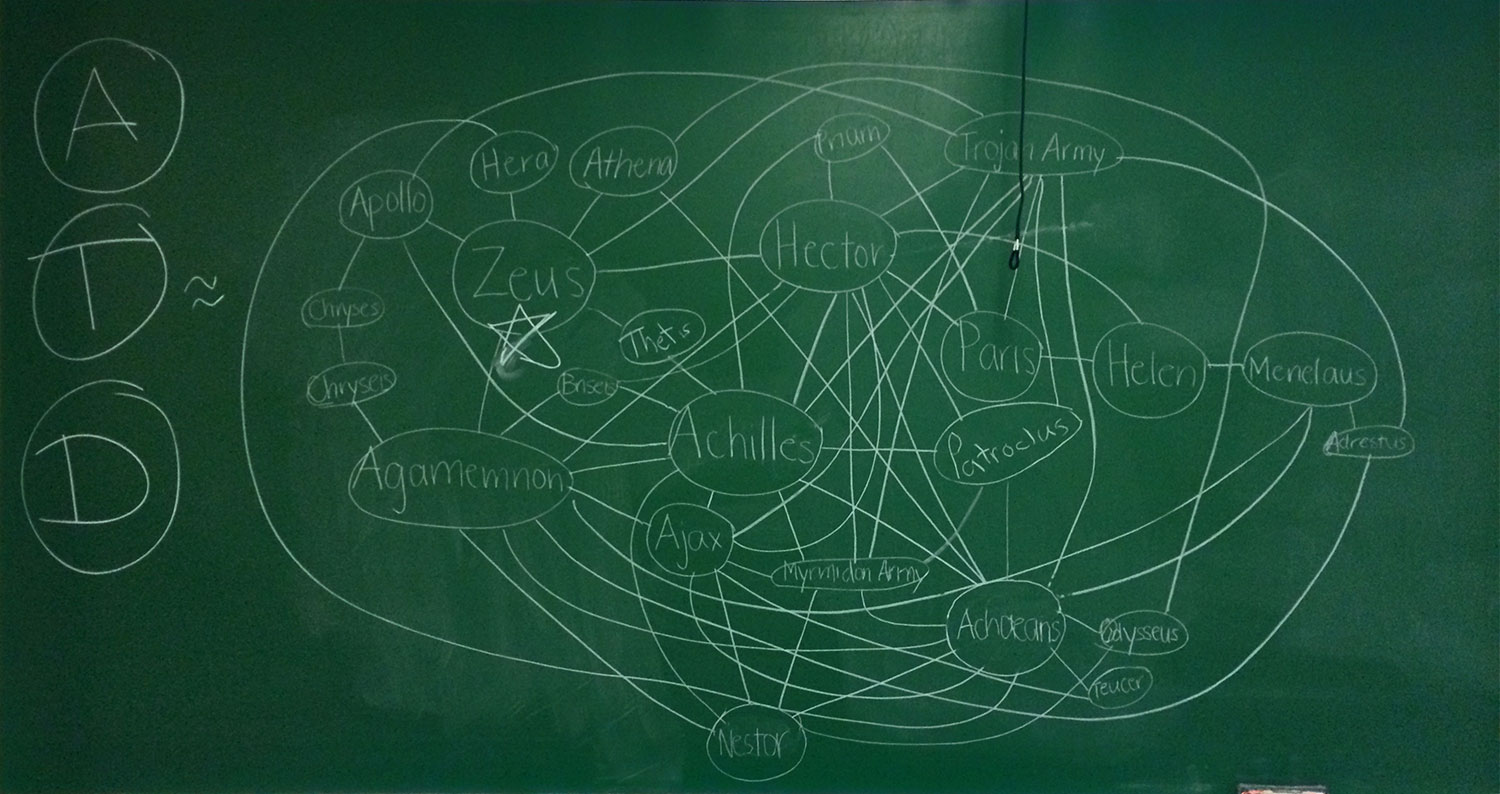

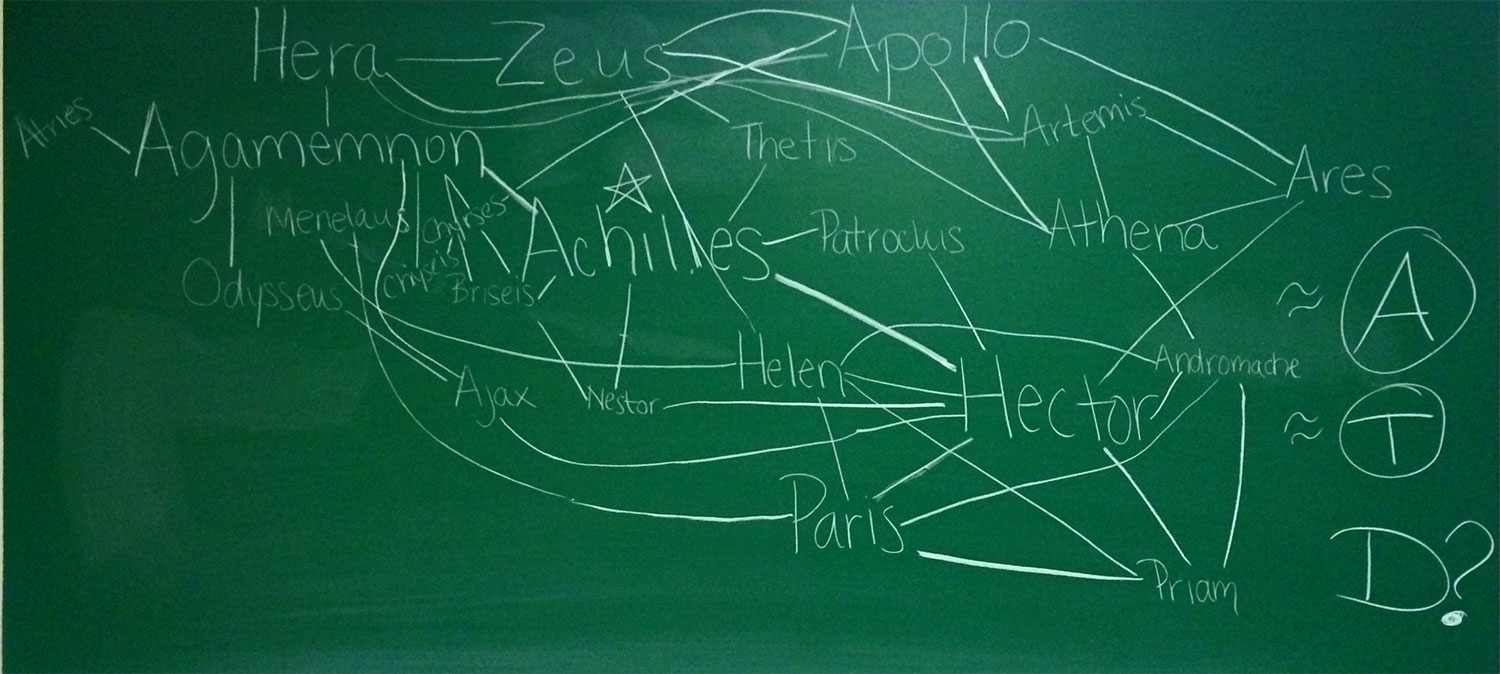

These images are of the three networks students drew in the Fall 2013 semester, which I use because the classroom was tiny, badly equipped for any class (much less a digitally inflected class), and possessed only of a single standard-size chalkboard and a companion half-size chalkboard for presentation purposes.

The starred starting points indicate which character the students in that group started with, and the A/T/D notations represent the class voting on whether that network represented an Assortative, balanced Triadic, easily Destructible network. A circled letter means they felt that network diagram was representative of that particular characteristic.

My Observations

This semester was my second time through this exercise, and one of the major differences between the two different explorations is the variation in how students saw the three characteristics expressed in the Iliad. Students last semester pitched a variety of network styles, with no group assuming the Iliad had all three characteristics. This semester, the groups sketched out their draft network and decided the Iliad met all three characteristics of a real social network. The voting also reflected their mostly successful attempts to represent that argument.

In part, that’s a result of the change in reading (last semester’s class read 3 fewer chapters and therefore worked with less data), and a response to my foregrounded emphasis on visualization as argument. I think, too, that it’s also the result of having one or two students in each group who asked to take a closer look at my Facebook-network visualization as a way of thinking about where to start placing characters from the Iliad.

The process itself spawned a lot of great discussion about which characters to include, how to manage the inclusion of gods and demigods alongside the human characters, and how different types of social interactions operated in terms of connection strength. It also helped them think more carefully about how relationships in the various parts of the network they were visualizing worked.

It’s not perfect, of course. For one thing, some of the prep I do in the introductory part of the session leads students to make some very particular moves in their initial analysis phase. For instance, I’m sure using a Facebook network visualization as the starting point for their visual pushed some of the groups to build a “real” network for the Iliad. I also postponed the discussion about the Iliad’s shifting internal context–from bronze age to iron age and back again–until the 4th session in the unit, which meant we didn’t talk as much about context as I’d have liked.

However, the act of creating these network graphs did let us talk about several things. We were able to talk in a more educated way about how Mac Carron and Kenna reached their conclusion that the Iliad and Beowulf were “real” (notably, by removing antagonistic relationships from the Iliad and by removing Beowulf from Beowulf). That led to a discussion about the kinds of computational requirements that would go into a more contextualized, statistically valid network analysis. Finally, the students themselves brought up some of the contextualization issues that are important when drawing conclusions about multiple sources from multiple time periods, because in the process of dealing with their networks, students had to beef up their knowledge about the various factions of Greeks and Trojans in the Iliad and compare that to what they had learned from Herodotus.