31 Jan 2017 update: A full article has been published as “Analog Tools in Digital History Classrooms: An Activity-Theory Case Study of Learning Opportunities in Digital Humanities”

If you haven’t read the Analog Tools Background and Assumptions post already, pop in and have a look around before reading this.

This lesson plan is a direct export of my own research interests. Text mining, and particularly corpus linguistics, have helped me think more carefully about historical change and continuity in medieval conflict resolution, and in how divine agency plays a role in conflict resolution. One of my classroom goals is to expose students to the kinds of things they’d do as professional historians, so finding a way to add text mining to my syllabi has been a personal goal. Doing so in classrooms that aren’t equipped with computers–or even whiteboards, in some cases–has meant some compromise, but the compromises exaggerate both the weaknesses and the strengths of text mining as a methodological approach, which makes for better discussion about the methodology after the activity ends.

Learning Outcome Goals for Students

- To become familiar with the idea of text mining to analyze a historical or literary document.

- To understand how thematic development plays a role in reader reception of a text

The Activity

A hand-produced word cloud. Yep, that’s right. I even allow them to use Wordle.

Which is cheating. Word clouds a la Wordle aren’t really text mining, if your definition of text mining is mathematically rigorous inquiries into the relationship between words in a large corpus of text. The visualizations Wordle in particular produces are obvious. They provide shallow, meaningless results. They’re just too easy.

But, done right, a word cloud is also the perfect digital tool for an analog classroom. It can be organized around pen and paper while still giving students an introduction to basic text-mining methodology.

For this exercise, the students themselves become topic modelers. They were assigned a close-read passage of one of three books in the Iliad (6, 7, or 8), and told to track, by hand, the number of times important characters and important themes show up. This pushes them to think analytically, since they have to decide what an important theme is and who important characters are. It also pushes them to think computationally by forcing them to quantify the threshold for character and theme appearance.

They take these numbers and compare them to the numbers their classmates generated for the same chapter. The discussion about their threshold for quantification is designed to get them thinking about the kinds of decisions that go into building a training process for a topic modeling program.

Then, they decide how to represent the importance of each theme and character. Some student teams have, in the past, chosen to do so manually. Others have used Wordle’s advanced option to generate a visualization, but based on the themes and weight assigned by the group. In that way, their hand-generated word cloud is decoupled from the blindly generated jumble of topics that just takes every word in a document and parses it.

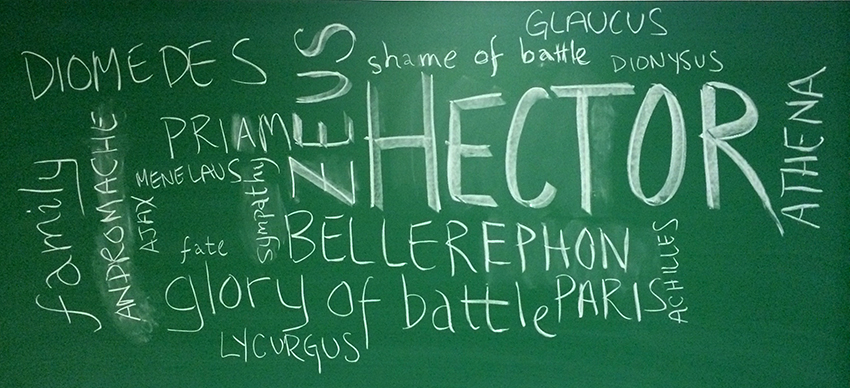

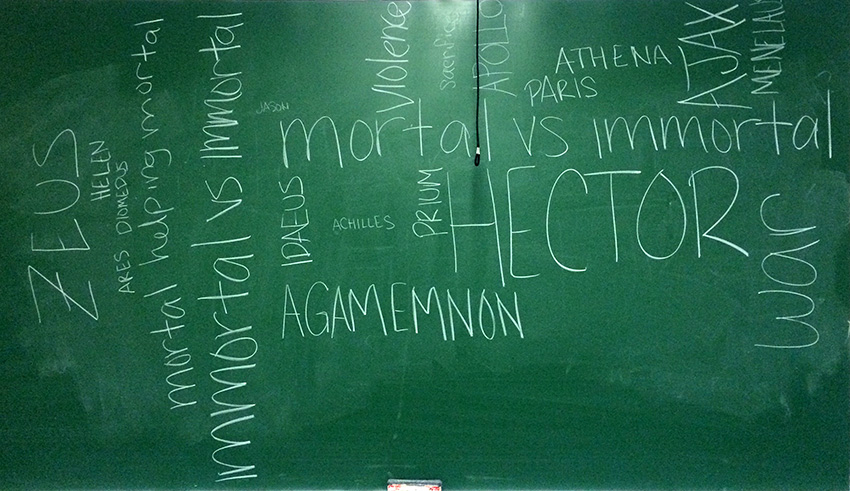

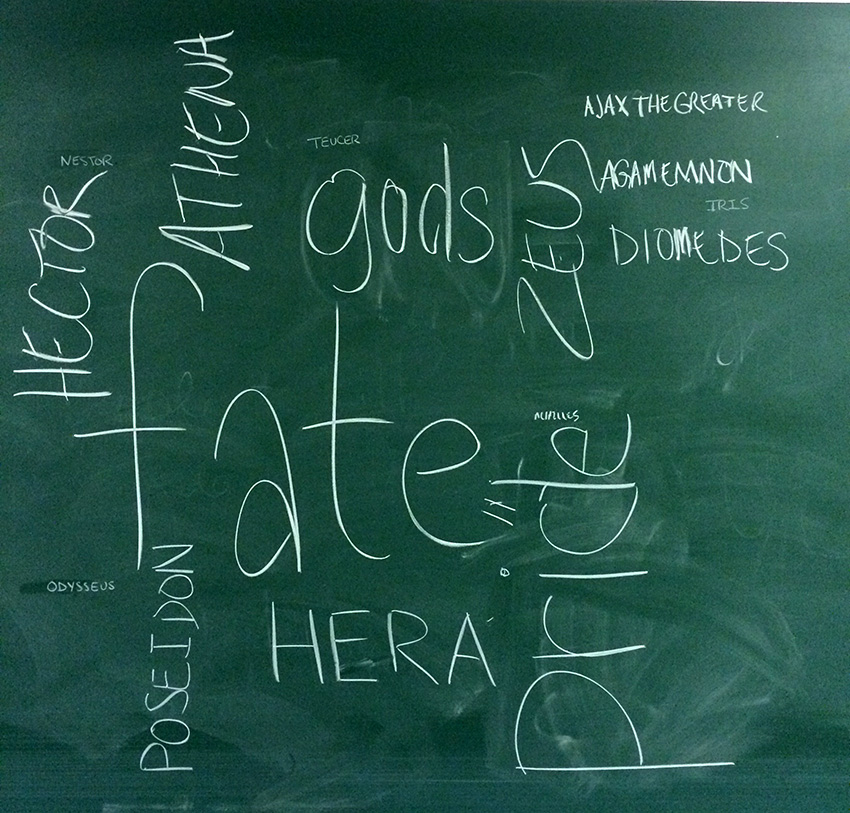

Finally, each group uses their word cloud to present the dominant themes and characters in their book. We then talk about the narrative construction of the chapters and how each book elicits specific responses from the reader in order to set up reader responses in subsequent books.

The Results

These images are of the three word clouds students drew in the Fall 2013 semester.

My Observations

While the word cloud approach isn’t a full foray into text mining, the systematic exploration of themes and characters has two advantages.

The word cloud approach gives students a systematic way to handle something many of them think of as ineffable. It seems to appeal to humanities students a way of questioning their intuitive approach to textual analysis, while non-humanities students gain access to a concrete set of values they can use to uncover and analyze narrative elements in a text. In either case, students who would otherwise have glossed over descriptions of Hector and his family come face to face with the Trojan’s humanity, with the enduring sense of familial love and respect that Priam and Hecuba have instilled in all of their children (except maybe Paris, who is “an ass”). Students see that familial bond broken by the capriciousness of the gods and the battle lust of the Greeks in books 7 and 8. For all that word clouds are a shallow approach to text mining, they do give students a way to engage with a text they previously saw as boring and unapproachable. Additionally, the engagement is more conscious, because as they work through the differences between their word cloud and the word clouds other groups in class generated, they become more aware of the emotionally charged nature of particular narrative choices.

Of course, “compact” and “text mining” don’t often co-occur, and students point that out. When I do this exercise, at least 1 student in each group asks how these kinds of text-mining approaches hold up in larger corpora of texts, and under the scrutiny of “traditional” textual analysis, and that gives us the chance to have a discussion about the importance of understanding your methodological choices and what kinds of conclusions you can come to. It’s nice to have this discussion again coming directly on the heels of the Iliad Social Network exercise, because we can talk about what kinds of analysis we can get out of the two methods, how we might use them together, and why we might want to.

Most importantly, I’ve found that the compact nature of this exercise–a single book in a single class session–makes text mining feel approachable. Getting students to engage when they’re dealing with the entirety of the Iliad via computer can be scary. Having students manually perform the task of a topic modeler on a limited corpus in a limited time frame means students take home a concrete skill, a gateway text-mining approach that they can (and do) use for their own analytical purposes.